Rampell: Actual Facts that Expose Trump's Recklessness on the Economy and His Failure to Deal with Affordability

Consumer confidence keeps falling, while inflation is up, and the costs of energy, health care and housing are spiking. Meanwhile, Trump's witless policies make things worse. Heckuva' job, Donnie.

By Catherine Rampell /The Bulwark

Like climate change and the Epstein files, the affordability issue is a “hoax.” So saith our president.

“The word ‘affordability’ is a con job by the Democrats,” Trump declared during last week’s cabinet meeting, in between snoozes. “The word ‘affordability’ is a Democrat scam,” he insisted, adding that the word “doesn’t mean anything to anybody.”

Sure, just last week he was proclaiming himself “THE AFFORDABILITY PRESIDENT,” but maybe he has a point. “Affordability” doesn’t have a universally agreed-upon definition. Is it just a vibe? A number? How can you tell if it’s getting better or worse?

So let’s talk about how you might go about measuring affordability, if you were trying to do so in an intellectually honest way, and what Trump could do to improve the issue. He’s probably not going to like the answer.

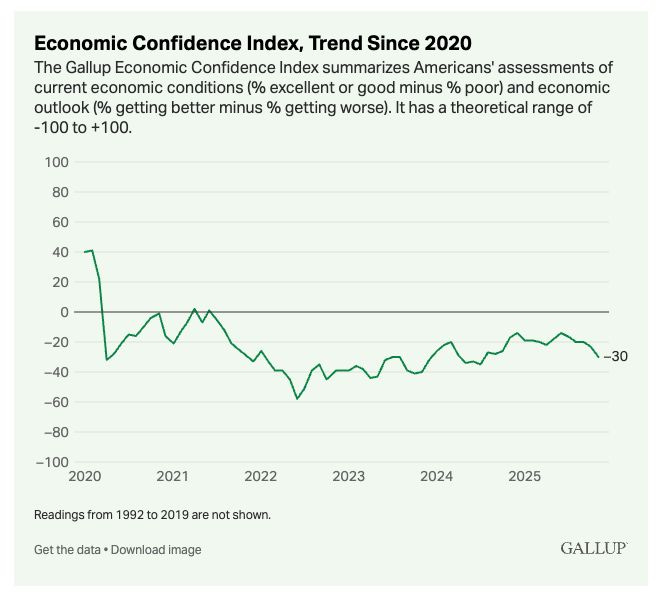

First things first. Yes, the vibes are definitely bad. Americans hate the economy these days, and have for a while.

Consider Gallup’s Economic Confidence Index, which was released on Dec. 5. This index looks at two measures: how many people rate the economy as “excellent/good” minus those who say “poor”; and the share who say the economy is getting better minus those saying it’s getting worse. This monthly measure has been consistently below water since 2021, and in November, it fell to a seventeen-month low.

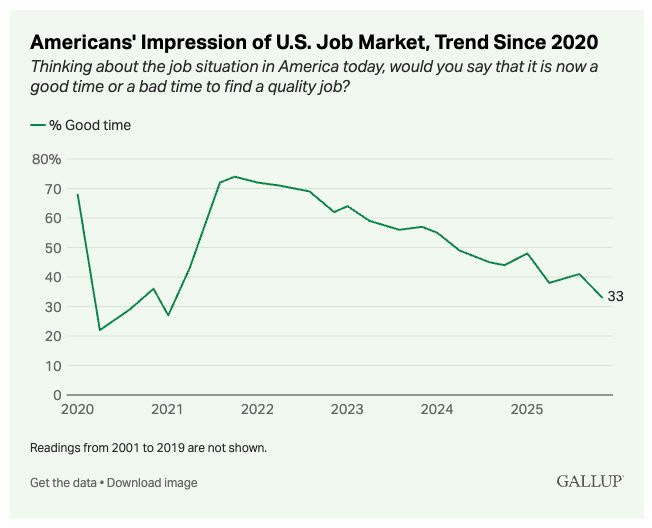

Gallup also found that Americans’ views of the job market are at their most negative since the end of Trump’s first term, when the pandemic was still raging. Consumers have likewise sharply revised down their expectations for how much they’ll spend this holiday season. In fact, their mid-season spending plans fell by the largest amount on record.

Other measures of consumer sentiment are similarly dour. For ten months, the Conference Board’s Expectations Index has tracked below the threshold that usually signals a coming recession.

But these are feelings, and as we know, facts don’t care about your feelings. So let’s look at some harder data.

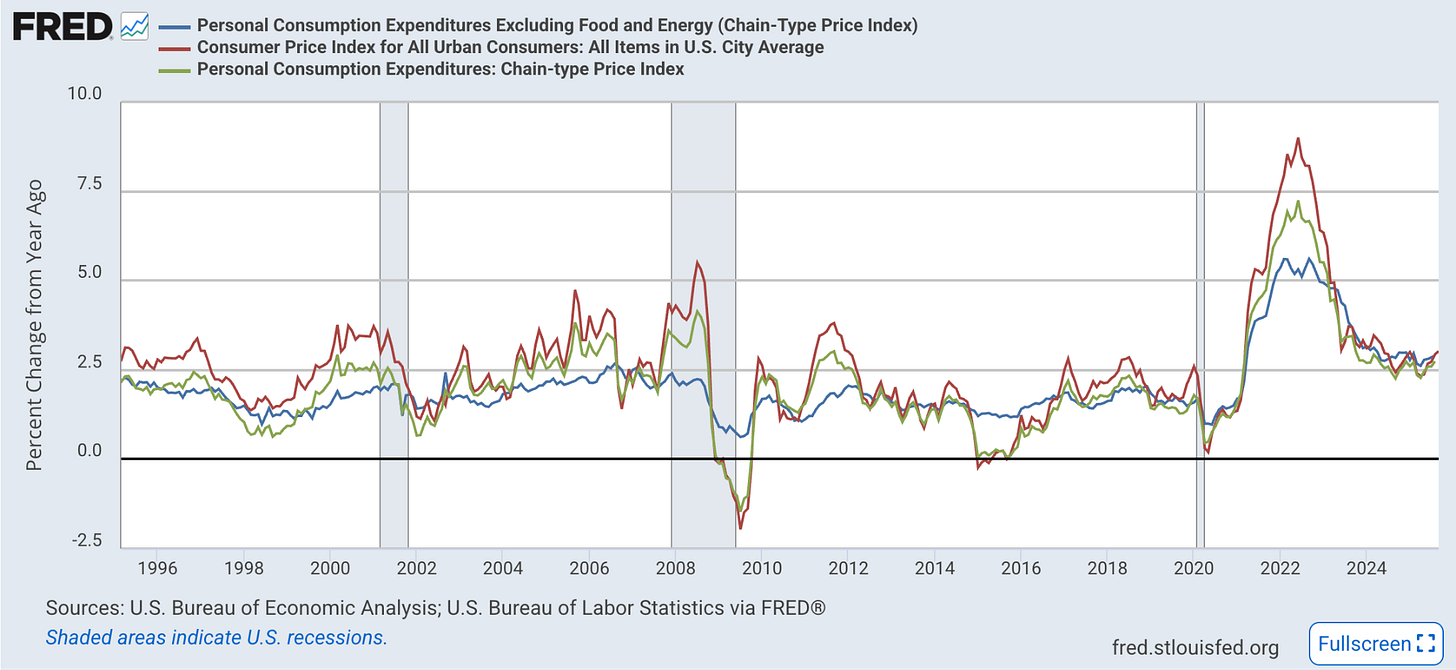

(Not) Fun with numbers. One obvious metric for assessing affordability might be overall inflation, which measures how quickly prices are rising. Inflation is now significantly lower than it was during its post-COVID spike, but it has been ticking up roughly since Trump’s “Liberation Day.”1

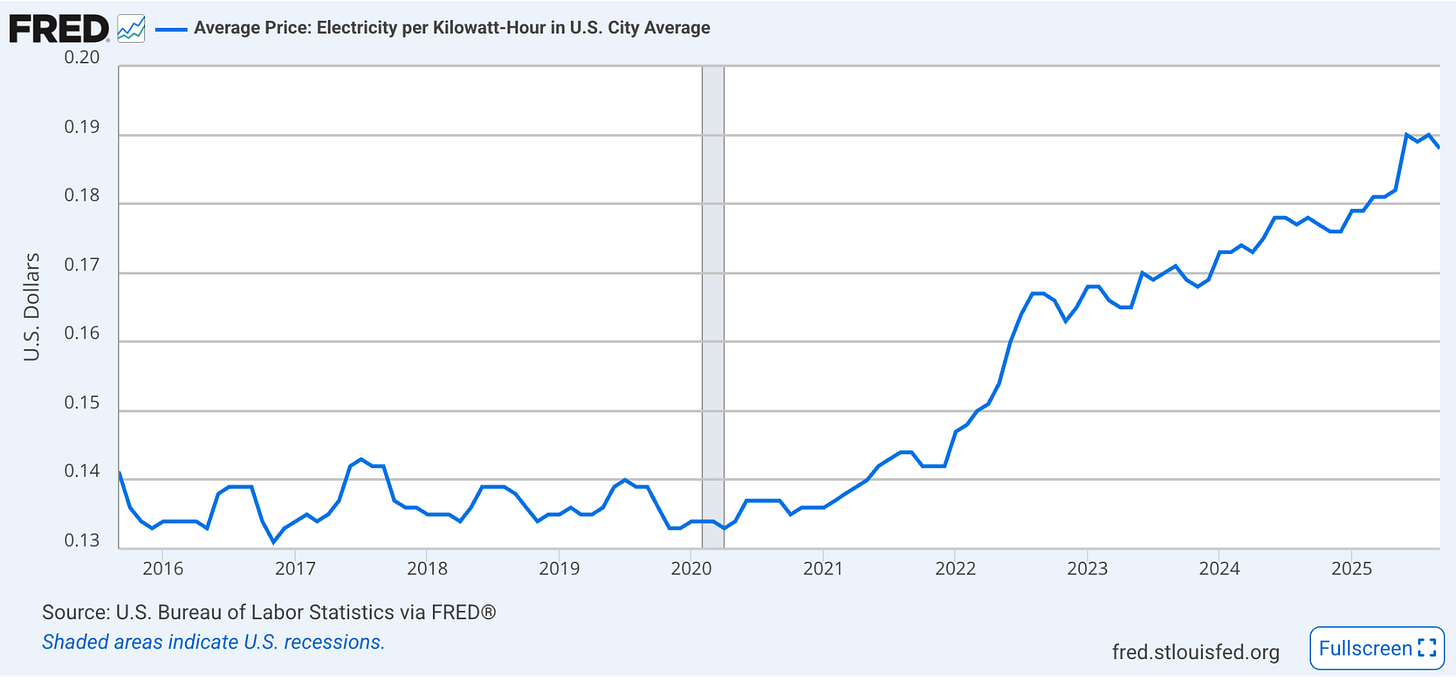

Or maybe you’d look at one specific, more salient expense, such as electricity, which played a big role in the recent off-cycle elections in New Jersey, Virginia, and Georgia. Electricity prices have indeed surged nationwide—both since the end of the pandemic and in the past year:

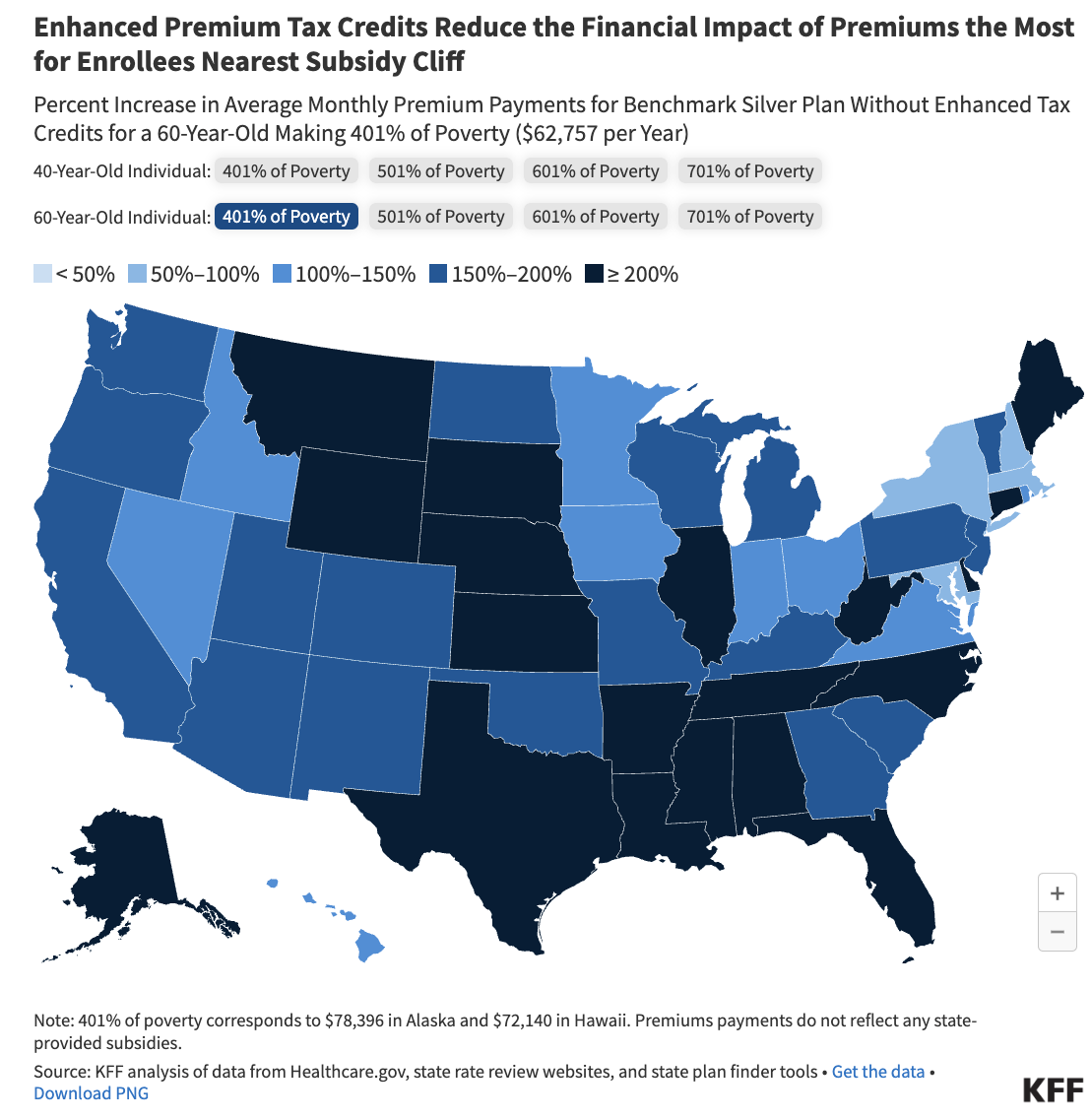

You might also look at health insurance, the key issue in the recent government shutdown. Chiefly because Republicans refused to extend Obamacare subsidies expiring this month, the average premium for people who get subsidized health insurance in the individual marketplace is expected to more than double (from $888 in 2025 to $1,904 in 2026).

Finally, you might also look at housing, the key to the American Dream.

House prices shot up during the pandemic, but more recently price growth has tapered off. That sounds like progress, except consumers are still of course having to confront all that previously accumulated price growth.

And that’s a common problem with assessing “affordability” based on traditional inflation metrics. Inflation is a measure of changes in prices, not levels of prices. So if the price of a basket of goods is not growing today but it grew a lot last year, inflation will look pretty low, even if the products in question still feel super expensive, or outright unaffordable.

Another way to look at all this is to examine what’s happened to wages after inflation2: How much more stuff can you buy than you could before? There’s an ongoing debate about the best way to measure inflation-adjusted wage growth, which we can discuss in greater depth another time.

Suffice it to say that on net, real wage growth has been somewhere between slightly negative and weakly positive in the years since the pandemic.3

That means people’s living standards have been stagnating—a problem that antedates Trump, but which he hasn’t helped.

So what can Trump actually do about this? The answer is not much, but ideally none of the things he’s currently doing.

It’s unhelpful, for instance, that Trump has jacked up tariffs to the tune of approximately $1,700 for the average household and $900 for households at the bottom of the income distribution, based on estimates from the Yale Budget Lab.

Also unhelpful is the cancellation of various energy projects around the country that might have helped push down electricity prices.

The president could also stop mass deportations of the agricultural workforce, which even his own administration says is a threat to “the stability of domestic food production and prices for U.S. consumers.”

Same with the construction workforce, which is needed to build more houses. Trump’s DHS blames “tens of millions of criminal illegals” for increasing every fathomable expense—housing, groceries, healthcare, etc.—but his deportation and de-documentation policies are likely contributing to high costs, given the sectors that immigrants are more likely to work in.

And he could definitely stop degrading the political independence of the Federal Reserve, as he’s been doing by trying to purge Fed officials he dislikes so he can install loyalists. In the long run, this is toxic for inflation.

There’s no knob under the Resolute desk that presidents can use to dial down prices, but there are a few isolated things Trump could do to help.

Extending the ACA subsidies, for instance, would shield people from a doubling of their premiums. But that might require acknowledging Democrats were right on the issue—which, of course, they can’t be because it’s all a fake news con job hoax.

1-Because of the government shutdown, the most recently available data are still somewhat old, alas.

2-Brookings just released a valiant attempt at quantifying “affordability,” based on how incomes compare to “basic necessities” in different parts of the country. But it’s a snapshot of 2023, rather than a time series that includes the current year.

3-By one measure, known as the Employment Cost Index, people are earning about the same pay that they were in 2020, after adjusting for inflation, maybe even a little less. By another metric, real wages are up. Reasonable people can disagree about which is the more relevant metric to use, depending on what you’re trying to capture.

Veteran columnist and media commentator Catherine Rampell serves as Economics Editor of The Bulwark, and writes its “Receipts” newsletter. Subscribe here.

Image: joeydevilla.com