June 29, 1925: The Day that Jolted Santa Barbara into History

On the 100th anniversary of the quake that changed the city forever, the clock is ticking for the next Big One.

By Melinda Burns, Special for the Santa Barbara News-Press

At about 6:42 a.m. 100 years ago today, the residents of Santa Barbara were violently tossed around — some thrown out of their beds — by the heaving of a mighty earthquake.

The shaking lasted 18 seconds. On State Street, the shock produced a giant wave that lifted entire buildings and then slammed them back down. Facades slid off, hotel guests were tossed out of rooms and 11 people were killed by falling debris. Sixty-five others were injured. The sky turned black with dust from the rubble.

Fissures three feet deep opened on the Coast Highway, and the concrete pavement buckled on Mission Ridge. The Sheffield Dam, an earthen structure on the other side of the front range, fell apart as the ground under it liquefied. A torrent of water 20 feet high — 45 million gallons in all — went raging down Sycamore Canyon to East Beach, dragging three homes, a car and 17 cows with it.

Amid the confusion, only a few people — a swimmer, a couple of men in a boat and, most notably, Pearl Chase, the civic leader — reported witnessing a likely tsunami, 10 feet high, that rushed in from the bay, spilled over the West Beach seawall and flooded Chapala and State streets nearly to the railroad tracks.

Throughout the town of 24,000, chimneys were sheared off at roof lines and homes slipped off their foundations. Beds, sofas and even pianos skidded across floors, and the glassware in kitchen cupboards flew through the air and shattered.

At the Santa Barbara Mission, witnesses said, a priest stopped 15 parishioners from rushing out of Mass as chunks of stone towers from the building fell to the ground outside.

A deafening roar — rocks grinding deep beneath the earth — preceded the quake by two or three seconds, one witness said, adding that he was “picked up and shaken as if some monster had me by the shoulders with the sole intent of shaking my head from my shoulders.”

Leaning on history. That’s a glimpse of the dramatic events of June 29, 1925, as described in a report for the quake anniversary by Larry Gurrola of Ventura, a Ph.D. engineering geologist.

On a mission to fill some gaps in the historical record, Gurrola spent weeks away from his day job this spring, digging into the archives of the Gledhill Library at the Santa Barbara Historical Museum — mainly, 100-year-old editions of the Santa Barbara Morning News and Santa Barbara Daily Press, precursors of the Santa Barbara News-Press. He found their reports more reliable and less prone to sensationalism than accounts elsewhere in the state.

“You come across a degree of exaggeration out of the area,” Gurrola said. “I focused in on the local papers. It seemed to be more accurate reporting, more consistent.”

The 1925 earthquake remains the most destructive in Santa Barbara history in terms of loss of life and property. It was felt as far north as Santa Cruz and as far east as Bakersfield.

An engineering committee of experts from around the country was brought in to conduct a survey in Santa Barbara. In all, 411 commercial and government buildings were damaged, the committee found, and 18 percent of them, or 74 buildings, were “total wrecks.”

The Board of Fire Underwriters of the Pacific counted a total of 618 buildings that had been damaged or destroyed. And in his search, Gurrola found there was more extensive damage to private homes than previously reported, particularly on the lower Westside.

In all, the damage was estimated by the engineering committee at $15 million, equivalent to nearly $275 million in today’s dollars.

Great unknowns. The historical record is rich in detail about the events of June 29, 1925, but there is much that will never be known.

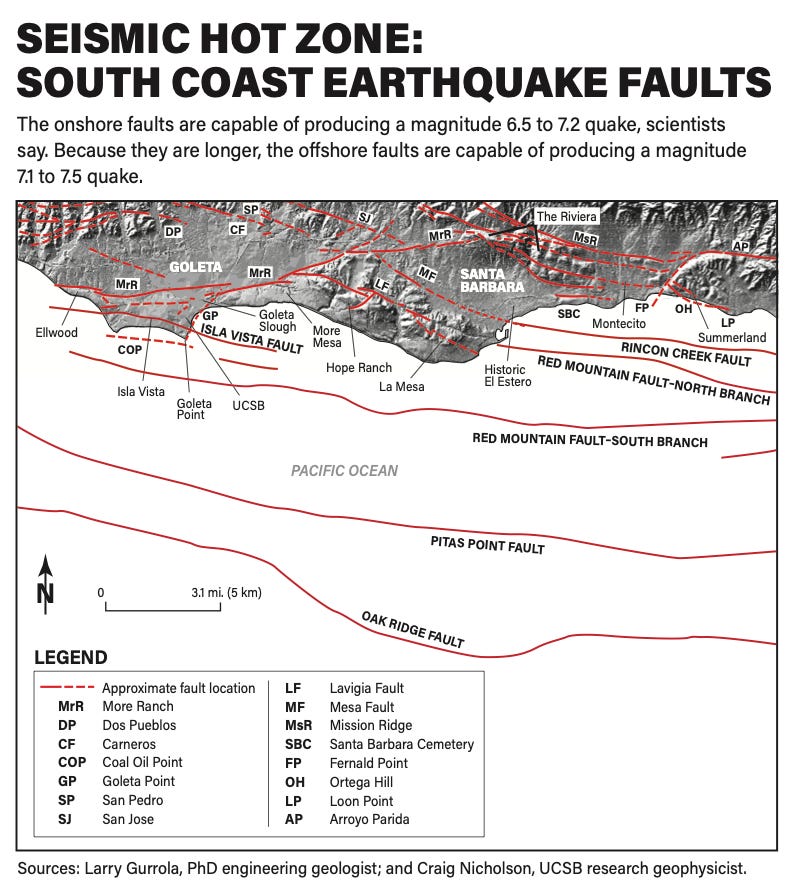

There is no scientific consensus about the size of the earthquake, where it began, whether one or more faults were involved, or what the length of the rupture was. The South Coast is underlain with a network of more than a dozen earthquake faults; and there are several longer, potentially more dangerous, faults offshore.

The record shows that Santa Barbara County has experienced 10 major earthquakes since 1806. They ranged from an estimated magnitude 7.0 quake in 1812 that decimated the La Purísima Mission near Lompoc, to a magnitude 5.9 quake in 1978 that damaged UC Santa Barbara.

Today, Gurrola and Craig Nicholson, a UCSB research geophysicist, will lead a group of scientists from the U.S. Geological Survey, California Geological Survey, Caltech and other universities on a field trip sponsored by the Statewide California Earthquake Center. They will look at South Coast earthquake faults, marine terraces and other evidence of quake activity in the local topography.

On Monday at UCSB, the group will exchange presentations on the 3-D geometry of the local faults and how they interact.

“There is a very strong debate about how large an earthquake the fault system in the Santa Barbara-Ventura area can produce,” Nicholson said. “The 1925 earthquake is still relevant.”

Size matters. The Richter scale, a measure of the power of earthquakes, was not invented until 1935.

Charles Richter placed the magnitude of the Santa Barbara quake at 6.3, using data recorded at distant stations. That number stuck until 1975, when the late Art Sylvester, a UCSB geology professor, elevated the quake to a magnitude 6.5, based in part on eyewitness accounts he had collected from 50 survivors.

In 2018, Sue Hough, a USGS seismologist based in Pasadena, compared the 1925 Santa Barbara earthquake with 1994's magnitude 6.7 Northridge quake, among others. She concluded that the 1925 event was probably a magnitude 6.5. But others have placed it as high as a magnitude 6.8.

“Different people are looking at different data,” Nicholson said. “It’s part of science. Right now, the most reliable number is 6.5.”

The Richter is a logarithmic scale. For each whole-number increase in magnitude, the seismic energy released in an earthquake increases by about 32 times. That means a magnitude 7 earthquake produces 32 times more energy — or is 32 times stronger — than a magnitude 6 quake.

That's why each decimal point matters. According to a USGS online calculator, a magnitude 6.8 quake is 2.8 times stronger than a magnitude 6.5.

In 1999, the late Ed Keller, a UCSB geology professor, and Gurrola, then his student, studied the sea cliffs on the South Coast, looking for signs of prehistoric quakes.

They discovered the land was being uplifted at a rate of 1 to 2 millimeters per year, about the thickness of a fingernail. Infinitesimal as it seems, that rate is indicative of a relatively high earthquake hazard — perhaps even a magnitude 6.8, they concluded.

The historical record, Gurrola says, supports a magnitude of 6.7 or 6.8 for the 1925 quake.

More eyewitnesses reported being knocked down by the impact than previously thought, he found. Those accounts, plus the extensive damage to the downtown, the lower Westside and Goleta — and especially reports of what is known today as a “ground roll” up State Street, at the La Cumbre Country Club, at the Rose Garden by the Mission, and on Mission Ridge — all point to a larger event, Gurrola said.

“The ground roll phenomenon was not previously known,” he said. “I was excited to find that. We can look at geology that’s thousands of years old; it tells us something. But really, it’s the recent history that gives us vital information about how the ground responded to the earthquake shaking. It helps us to identify the areas that liquefy.”

One of those, Gurrola said, is the Funk Zone, a district of popular restaurants, wineries, breweries and art galleries between Garden Street and the waterfront at Cabrillo Boulevard, bounded on the west by State Street. It’s where the El Estero, the former slough, was used as a dump for earthquake rubble and garbage and was later filled in for development.

“The Funk Zone is a cool place to go,” Gurrola said. “You just don’t want to be there in an earthquake.”

The next Big One. The epicenter of the 1925 quake has not been identified. Scientists have pointed, variously, to the Mesa, Mission Ridge and More Ranch faults onshore, and the Rincon Creek fault offshore, or some combination of these.

Gurrola, who studies the onshore faults, believes the quake occurred on the Mission Ridge fault system, which includes the More Ranch and Arroyo Parida faults and extends from Ellwood to Ojai. If all of these segments ruptured at once, he said, the result would be a magnitude 7.2 quake. But a Northridge-style quake would be more characteristic of the onshore faults, Gurrola said.

Nicholson said that, in combination with the onshore faults, the offshore fault system is capable of producing larger earthquakes of magnitude 7.4 or 7.5. That’s because the onshore south-dipping Mission Ridge and Mesa faults have merged with the offshore north-dipping Red Mountain and Pitas Point faults to form a “master” fault deep below the ocean floor, he said.

It is this complex system of interacting faults that was responsible for the Santa Barbara earthquakes of both 1925 and 1978, Nicholson said. The Red Mountain and Pitas Point faults are part of an even larger fault system that extends 75 miles from Ventura to Point Conception.

Speaking June 9 to a sold-out crowd at Dargan’s Irish Pub & Restaurant in Santa Barbara, Gurrola explained why the city is in an active earthquake zone. There’s a big bend in the San Andreas Fault, he said, where the North American and Pacific plates are colliding with each other, not moving but rather getting squeezed. It’s just west of Frazier Park.

The stored-up energy in the earth’s crust in Santa Barbara will periodically cause the faults to slip. The resulting quakes have created the hills and valleys of Santa Barbara, including the Mission Ridge and Sycamore Canyon, and the Mesa and Goleta Slough, Gurrola said.

County history goes back only 250 years, he told the crowd, but it shows “we’re getting one big earthquake in a century.”

Nervous laughter ensued as everyone mentally added 1925 plus 100.

“Is it time to sell my house?” someone asked, to more laughter.

The good news. Albert Einstein, the great theoretical physicist, once said, “In the midst of every crisis lies great opportunity.”

That was true for Santa Barbara in 1925.

From the outset, the city had some luck. When the quake hit, two quick-thinking men — Henry Ketz at the Southern Counties Gas Co., at Montecito and Quarantina streets, and William Engle at Southern California Edison on Castillo Street — cut the gas and power to the entire town. That prevented a conflagration such as the one that burned down San Francisco after the magnitude 7.9 quake of April 18, 1906.

In San Francisco, the fire caused more damage than the shaking did.

But after the 1925 quake in Santa Barbara, architects and engineers were able to study the damage and identify what worked and what didn’t. The lessons they learned became the impetus for the first national uniform building code, developed in 1927. Crucially, it incorporated requirements for supports strong enough to withstand horizontal shaking.

In 1930, the Santa Barbara City Council lowered the maximum allowable height of commercial buildings to four stories, or 60 feet. In 1972, the voters enshrined the height limits in the City Charter.

In 1986, California changed the state building codes to require seismic retrofits of brick buildings in earthquake-prone areas. If — or more likely, when — a major earthquake occurs in Santa Barbara again, those retrofits may not save the older buildings from irreparable damage, but they will save lives.

Today, many of the older homes in Santa Barbara have been bolted and strapped to their foundations. Some homeowners have removed their brick chimneys too.

Best of all, after the quake of 1925, the city got a makeover.

Civic leaders, including Pearl Chase, had long dreamed of a downtown built in the “Spanish colonial revival” style, with red-tiled roofs, arched doorways and pedestrian “paseos,” thick white plaster walls and deep window recesses. Now, they saw their chance.

“There are good things that come from earthquakes,” Nicholson said. “There was a silver lining in the case of Santa Barbara. It redefined itself as this beautiful coastal city with a very dramatic architecture and design.”

Even Santa Barbara’s new police station will reflect the legacy of 1925.

To meet the state’s higher earthquake standards for “essential services facilities,” the building will have solid concrete walls and a frame of extra-thick steel columns and beams, Brian Cearnal, the project architect, said.

The site, at Cota and Santa Barbara streets, is currently undergoing soil preparation. To support the slab foundation, Cearnal said a grid of enormous holes 8 feet across and 20 feet deep will be dug into the ground and filled with a thick mix of water, cement and soil. It’s a soil-strengthening system called “deep soil mixing.”

“The codes have just gotten increasingly more strict, relative to earthquake safety,” Cearnal said.

The station will have a basement and three stories within the city’s height limits. It is not located in the downtown area designated as Pueblo Viejo, where Spanish colonial design is mandated, Cearnal said, but it will have a red tile roof, plaster walls, copper gutters and wrought-iron railings and lighting.

“We obviously felt this was an important civic building of Santa Barbara and we needed to reflect that,” he said. “In Santa Barbara the expectation is our buildings have a certain amount of romance and charm.”

A police station with charm? It all goes back to 6:42 a.m., 100 years ago today.

Melinda Burns, a former senior writer for the legacy Santa Barbara News-Press, is an investigative reporter with 40 years of experience covering immigration, water, science and the environment. In 2000, she covered the 75th anniversary of the Santa Barbara quake for the paper, interviewing a few survivors who had been children when it happened. One of them recalled going wild with delight when the Wilson School crumbled to the ground.

Today’s events (Sunday, June 29) marking the 100-year anniversary

Day of Remembrance: Religious leaders will gather on the steps of the Santa Barbara Mission to offer short prayers and reflections about community loss and resilience. The official design for the centennial plaque will be unveiled. The service will conclude with the ringing of bells throughout the city. The event is free and open to the public. 2-3 p.m., Santa Barbara Mission

Earthquake symposium: The Santa Barbara chapter of the American Institute of Architects presents "The earthquake that built a city," a special 90-minute symposium exploring how disaster gave rise to the vision, resilience and distinctive architectural identity of Santa Barbara. The event is sold out, but guests can contact the Lobero Theater box office at (805) 963-0761 or boxoffice@lobero.org, to check last-minute availability. 5-8 p.m., Lobero Theater

March 24, 1806: This quake caused extensive damage to the Presidio Chapel and cracked three walls of the chapel at the Santa Barbara Mission. Magnitude: Unknown

Dec. 21-22, 1812: This was one of the strongest earthquakes in Southern California history and may have originated in the Santa Barbara Channel. Severe shaking reduced to “rubble and ruin” the La Purísima Mission in Lompoc, about 55 miles north of Santa Barbara, and the Santa Barbara Mission was damaged beyond repair. The Santa Barbara Presidio also was damaged, and soldiers built thatched huts near the Mission to live in for the next three months. José Arguello, the Presidio commander, reported that there were tremors through Jan. 14, 1813, and that the ground opened up at several places (he did not specify where), creating sulphur-spewing volcanos.

The Santa Ines Mission, San Buenaventura Mission and San Fernando Mission in Mission Hills, 140 miles south of La Purísima, were damaged. A tsunami was reported on the South Coast of Santa Barbara County, likely triggered by a massive underwater slide. In one eyewitness news report, a Santa Barbara resident described how the sea receded, leaving the shore dry “for a considerable distance” and how it returned “in five or six heavy rollers, which overflowed the plain on which Santa Barbara is built.” The Chumash abandoned villages on Santa Rosa Island. Magnitude: 7.0

July 27-Dec. 12, 1902: A series of sharp, violent shocks collectively known as the Los Alamos earthquake struck the town on July 27, damaging two large tanks of oil totaling 125,000 gallons. One of the shocks was likened to the report of a thousand cannons. A small river of water began flowing in Los Alamos Creek, which had been dry for several years. On July 31, two more quakes hit, damaging every house and toppling every chimney in town. Fissures and cracks appeared in the ground. The “epidemic of earthquakes” lasted months. Magnitude: 6.0

June 29, 1925: The Santa Barbara earthquake is the most destructive in the city’s history in terms of loss of life and property. Eleven people were killed by falling debris. Two of them, guests at the Arlington Hotel, were crushed by a 25,000-pound water tank that crashed through the roof. It had been placed there for safety reasons, in case of fire. The Sheffield Dam cracked apart, releasing 45 million gallons of water to the ocean at East Beach. Eighty percent of the commercial buildings in the city were damaged or destroyed, piling so much rubble on State Street that travel by car was impossible. More than 600 buildings were damaged or destroyed, including 400 large commercial and government buildings. The damage was estimated at $15 million — about $275 million in today’s dollars. Magnitude: 6.5-6.8

June 29, 1926: A strong aftershock of the 1925 quake, one year later to the day. The Santa Barbara downtown was moderately damaged, and one person was killed. Magnitude: 5.5

Nov. 4, 1927: The Lompoc earthquake. The epicenter was offshore; some scientists believe it was about 28 miles west of Point Conception, and others place it closer to the coast. Three smaller quakes followed within 30 minutes. The temblor shook ships on the ocean, but it was felt most intensely in western Santa Barbara County, particularly in Lompoc, Santa Maria and Los Alamos, where chimneys collapsed, windows cracked and the cornices of buildings fell to the ground. A well-documented tsunami 8 feet high was generated along the North County coast. Several hundred thousand cubic feet of sand under the tracks of the Southern Pacific Railroad shook loose and fell to the beach below. Service was interrupted until repairs could be made. Magnitude: 7.0

June 30, 1941: The epicenter of this quake was centered in the Channel, about six miles south of Santa Barbara. Downtown buildings, especially those that had not been adequately repaired after the 1925 quake, suffered extensive damage, as scores of store windows were smashed and brick facades were toppled. Thirty glass-topped street lamps were snapped off, and water mains suffered 17 breaks. In Carpinteria, about 25 chimneys collapsed. Damage was estimated at $100,000, most of which was to drug and liquor stocks and plate glass. Magnitude: 5.9

July 21, 1952: The Tehachapi earthquake originated in Kern County and caused $400,000 worth of damage to downtown Santa Barbara. Like all the great quakes, this one was noted for strong, slow ground oscillations that can cause damage at considerable distance from the epicenter. The Santa Barbara County Courthouse was reported to have “rocked like a rocking chair.” The Carrillo Hotel and Balboa building suffered the most damage. Liquefaction was reported along Laguna Street in the historic El Estero. Magnitude: 7.7

July 5, 1968: A swarm of 63 minor quakes occurred in the Channel, midway between Santa Cruz Island and Santa Barbara, between June 26 and Aug. 3. The largest caused $12,000 in damage in Santa Barbara and Goleta. Magnitude: 5.2

Aug. 13, 1978: Starting in March 1978 and continuing sporadically through July 1978, a swarm of microquakes occurred beneath the northeastern end of the Santa Barbara Channel. Toward the end of the swarm, at the end of July and in early August, Santa Barbara residents complained of an unusually large amount of oil and tar on local beaches. On Aug. 13, an offshore fault south of Santa Barbara abruptly ruptured, focusing its energy in a northwest direction, toward the Goleta Valley. Most of the shaking occurred between Turnpike and Winchester Canyon roads.

The damage was estimated at more than $7 million, primarily at UC Santa Barbara. Ten of 50 permanent buildings on the campus were damaged, and one-third of the books in the university library — some 400,000 volumes — were thrown to the floor. The Santa Barbara airport terminal was leaning. More than 300 mobile homes were damaged, including many knocked from their pedestals, rupturing gas, water and electrical connections. A landslide blocked San Marcos Pass. Ten minutes after the quake, a freight train derailed at a kink in the tracks in Goleta. In all, 65 people were treated for injuries. Magnitude: 5.9

— By Melinda Burns, Special to the Santa Barbara News-Press

Sources: UCSB catalog of “Santa Barbara Earthquakes, 1800 to 1960,” compiled and edited by the late Art Sylvester, UCSB professor emeritus in geological sciences; Sylvester’s “Earthquake Swarm in the Santa Barbara Channel, California, 1969“; “Final Report, July 2000, Earthquake Hazard of the Santa Barbara Fold Belt, California,” by the late Ed Keller, a UCSB professor of earth science and environmental sciences; and “Commemorating the 100-Year Anniversary of the June 29, 1925 Santa Barbara Earthquake,” by engineering geologist Larry Gurrola, Ph.D.

Photos: 1-This photo of workmen casually posing in the ruins of the Hotel Californian at 35 State St. remains the most iconic image of the devastation wrought by the great Santa Barbara quake (Photo courtesy of the Gledhill Library, Santa Barbara Historical Museum); 2-The Santa Barbara Daily News was without power, but this one-page first edition hit the streets between 10 and 11 a.m. on the day of the quake. Five hundred copies were printed using antiquated hand-set type and a hand-powered press. By early afternoon, the paper had secured a gas generator from Ott’s Hardware and was able to print 10,000 two-page copies of second and third editions. (Photo courtesy of the Gledhill Library, Santa Barbara Historical Museum); 3-The quake created displacement and fissures in the Coast Highway, shown here just east of State Street, looking west toward the Mesa. The Boyd Lumber & Mill Co. at 36 E. Mason St. is at center, with the Union Feed & Fuel Co. at 17 Anacapa St. left of center. (Photo courtesy of the Gledhill Library, Santa Barbara Historical Museum); 4-This house was knocked 3 feet off its foundation, and the chimney collapsed. Note the location of the front walk compared to the front door. (Photo courtesy of the Gledhill Library, Santa Barbara Historical Museum); 5-Two people were killed in the 1925 Santa Barbara earthquake when a water tank fell through the roof of the Arlington Hotel, a massive and pretentious structure that had been cheaply built at State and Victoria streets. (Photo courtesy of the Santa Barbara Historical Museum); “Our Restive Earth” (Photo courtesy of the Gledhill Library, Santa Barbara Historical Museum).