Cohn: As Measles Outbreak Rages, RFK Doubles Down on Reckless Quackery

Twenty-five years ago, the U.S. effectively eliminated measles in the country. Now rates are spiking, fueled by Kennedy's anti-vaccine, anti-science crackpot theories, policies and appointees.

By Jonathan Cohn /The Bulwark

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. rambled through a long list of topics when he spoke at the White House during last week’s cabinet meeting.

He talked about dietary guidelines and rural health care. Prescription drugs and medical research. He even mentioned hospital price transparency, which is one of the more obscure parts of his portfolio as Secretary of Health and Human Services.

But there was one subject Kennedy skipped, in an omission as disturbing as it was conspicuous. He didn’t say a word about the measles outbreak in South Carolina, which is the nation’s biggest in decades.

As of Jan. 28, the South Carolina Department of Public Health had logged more than eight hundred cases of the highly contagious disease, with many more unreported infections presumably out there because not all parents seek formal medical care for their kids. The official tally is now growing by more than a hundred cases each week and has blown past the count from last year’s Texas outbreak, which killed three people, including the first two American children to die of measles in a decade.

“This is a milestone that we have reached in a relatively short period of time, very unfortunately, and it’s just disconcerting to consider what our final trajectory will look like,” South Carolina state epidemiologist Linda Bell said during a briefing on Wednesday.

South Carolinians aren’t the only ones who should worry.

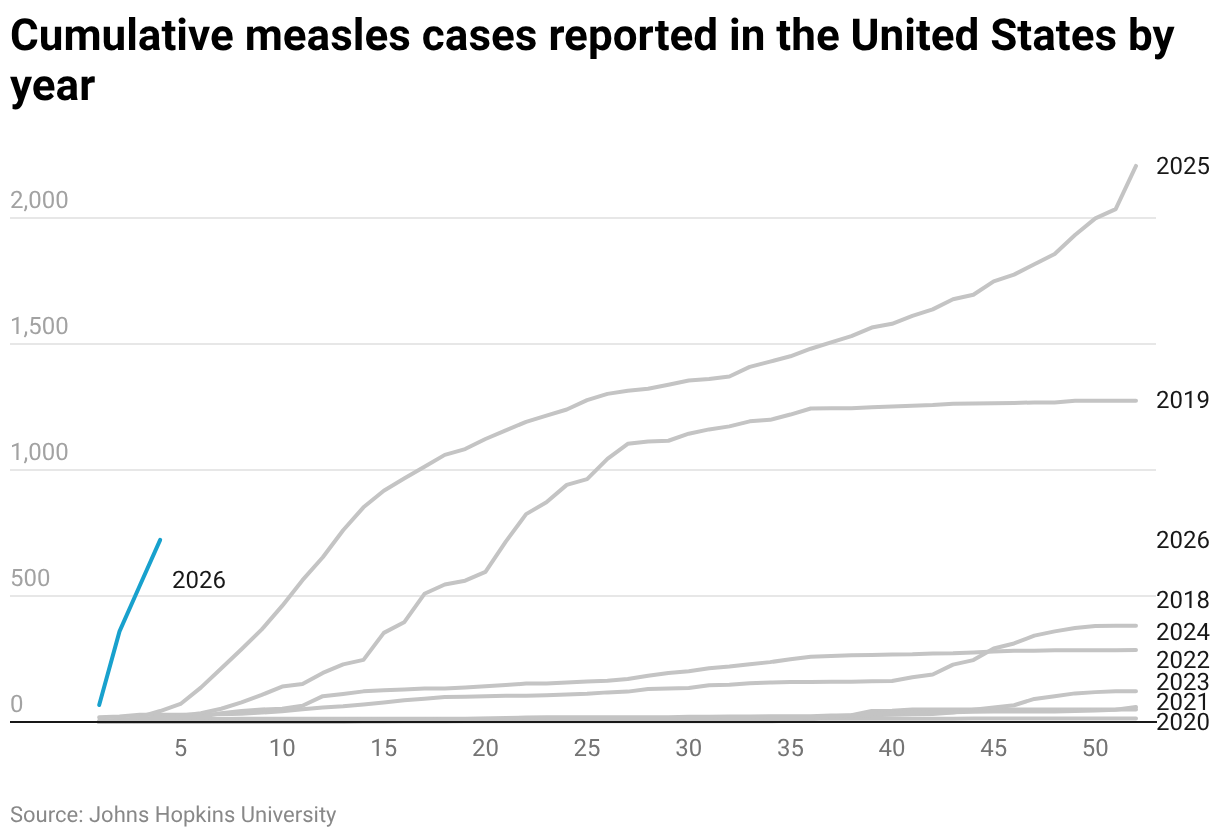

It’s in California, too. On the other side of the country, officials in Washington state say several new cases there are from travelers who picked up the disease while in the Palmetto State. Measles is also popping up in other states, including California, Florida, and Ohio. Overall the national measles count is on pace to shatter last year’s total, which was the highest since 1991.

This sort of recurring transmission of measles cases within U.S. borders represents a medical regression. In 2000, the United States achieved “elimination status,” which meant the disease was no longer circulating on a regular basis. The unvaccinated could still bring infections back after getting exposed abroad, but the illness wouldn’t spread far because the vast majority of Americans were immunized. The spark found no kindling, and between 2000 and 2024 the average number of cases stayed below 200.

Now that no longer holds true, which is why this year the United States is likely to lose its elimination status—a development that Kennedy and his allies are taking with mystifying nonchalance.

“Cost of doing business.” At a mid-January press briefing, a reporter asked CDC Deputy Director Ralph Abraham directly whether he was concerned about the United States losing elimination status. “Not really,” he responded, explaining that it was the “cost of doing business” in a world of global travel—as if global travel weren’t as much of a reality five or ten years ago, when measles transmission here remained rare.

Abraham’s indifference echoed something Kennedy said last year, at another cabinet meeting, following the first death from that Texas outbreak. When asked by a reporter about a child who had died, the first U.S. measles death in a decade, Kennedy downplayed the episode, saying “it’s not unusual. We have measles outbreaks every year.”

Later, as the outbreak got bigger—and as local officials were practically begging the unvaccinated to get vaccinated—Kennedy offered only delayed, grudging endorsements of the shots while continuing to question their safety. He also talked up the value of alternative therapies popular with vaccine skeptics like cod liver oil and vitamin A, which didn’t stop the outbreak but did lead to some cases of vitamin A toxicity.

Dismantling public health defenses. Back then, Kennedy was still new on the job, his confirmation hearing vows not to undermine vaccinations still reverberating through Washington.

But he has proceeded to do exactly what he said he would not do, dismantling federal defenses against infectious disease through a combination of personnel and policy upheavals. Now, with the South Carolina outbreak, we are seeing for the first time how these changed and weakened defenses respond to an actual crisis—or, more precisely, how they do not respond.

It’s a story that should be a bigger part of the political conversation, both because lives are in jeopardy and because the problem is directly related to who’s running the show in Washington, D.C., right now.

“The situation with measles right now is stunningly stupid,” Jennifer Nuzzo, a Brown University epidemiologist who runs their pandemic center, told me. “Countries like ours absolutely should not be having measles outbreaks in this day and age, period.”

Measles: not a joke. Many American think measles is no big deal, an impression Kennedy routinely reinforces. And the majority of people who get the disease really will be okay after seven to fourteen days of rashes, high fever, and other relatively moderate symptoms, which is why the screenwriters of a 1969 Brady Bunch episode—made famous in syndication—could play it for laughs.1

But for plenty of people measles is no joke.

It can lead to complications like dehydration and difficulty breathing severe enough to force hospitalization. It can cause encephalitis (swelling of the brain) and pneumonia, which is the main reason that between one and three out of every thousand children who get measles will die.

During the decade before 1963, when the vaccine first became available, the annual toll in the United States was, on average, 48,000 hospitalized, 1,000 diagnosed with encephalitis, and between 400 and 500 dead.

And those numbers, grim though they are, don’t take into account the disease’s long-term effects, which can include blindness, hearing loss, and a condition where the body literally forgets how to fight certain diseases.

Measles can also cause subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), which appears years after infection as a series of severe neurological problems including seizures, involuntary movements, and early dementia. A school-aged child in California died from that just a few months ago.

Elimination of elimination status. Introduction of the vaccine greatly reduced the spread of measles, and the introduction of a more effective, two-dose regimen in 1989 more or less wiped it out over the course of the next ten years, thanks in part to an aggressive public education and distribution campaign.

But at almost the very moment “elimination” status was achieved—a quarter century ago—the vaccination rate started to slip. Then, within the last decade, it started to fall more dramatically. And it’s done so unevenly, with anti-vaccination sentiment rising more in some communities than others.

“What’s going on is that there are pockets of [population] that have really low vaccination rates,” Katelyn Jetelina, chief writer for the Your Local Epidemiologist newsletter and an adjunct professor at Yale, told me.2 “And because measles is the most contagious virus we have on earth, it’s going to find those pockets.”

Vaccines in some respects are a victim of their own success, as people forget how awful diseases like measles could be. Another big factor has been a general loss of faith in the medical establishment that grew worse after the COVID-19 pandemic, when significant numbers of Americans became convinced that public health officials were giving unsound advice and dictating unjustly how people could live their lives.

Kennedy’s firehose of misinformation. Lurking behind all of this—and impossible, really, to separate from it—has been a flood of misinformation about vaccines that Kennedy spent many years circulating and is now, as HHS secretary, giving the government’s official endorsement.

Thanks to a change Kennedy ordered last year, a page on vaccine safety now says that “studies supporting a link [between vaccines and autism] have been ignored by health authorities” (they haven’t) and that the CDC’s long-held position that vaccines are safe is “not an evidence-based claim” (it is).

Perhaps more consequential have been Kennedy’s changes to the official advisory committee on vaccines, where he unceremoniously replaced the outside scientists who had been serving on it with a roster more sympathetic to his worldview. To lead the board, Kennedy appointed a pediatric cardiologist with a record of criticizing vaccine mandates, who said during a January podcast that it might be time to stop school mandates not just for measles but also for polio.

And it’s not just personnel Kennedy has changed. It’s policy, too.

The CDC has since December dialed back the guidelines for a half-dozen vaccines, taking away recommendations that everybody get them and instead urging consultations with doctors. Thanks to this change, the official childhood vaccine schedule now looks like the list from Denmark—a tiny country, not especially comparable to the United States, which recommends far fewer shots than most of its European counterparts.

After each one of these developments, public health experts warned that the cumulative effect of this rhetoric and these policy shifts would be to undermine faith in vaccines—both in the public generally and among strong Trump supporters specifically.

“If 30 percent of the country has that point of view and all of a sudden our vaccine coverage goes down, [outbreaks are] not going to be a statistical error,” Demetre Daskalakis, the former CDC official who resigned last year in protest and is now medical director at New York’s Callen-Lorde medical center, told me. “This is going to be ‘Welcome to our new reality of measles in America.’”

That sounds a lot like what’s now happening in South Carolina.

No way to protect babies. The outbreak has been concentrated in the northwestern part of the state, mostly (so far) in areas of Spartanburg County where vaccination rates in schools have dropped below the 95 percent level generally considered adequate for herd immunity.

In at least one of the schools with cases, the reported vaccination level is close to 20 percent. Several clusters are in local enclaves of immigrants from Eastern Europe, where a distrust of central authorities rooted in Soviet-era experiences was reinforced a few years ago by Russian authorities rushing their COVID shots to distribution before full safety testing.

But it’s not just schools in these ethnic pockets where people appear to be getting sick. Epidemiologists have been tracing exposures in churches, restaurants, gyms, and big box stores—as well as at the Greenville-Spartanburg Airport and Clemson University.3

Some clinics and physician offices have taken up preemptive practices like asking anybody with possible symptoms to stay in their cars and get tested there rather than come into waiting rooms where they could infect others.

Health professionals taking these steps are worried not just about people who have chosen not to vaccinate themselves or their children, but also about people unable to get the shot (which uses a live, weakened virus) because they are immunocompromised.

And then there are all the babies who within a few months lose the immunity they acquired in utero and don’t typically get their first doses until they reach their first birthdays, because that is when the shot’s effect becomes more lasting.

“If you’re a parent and you have a child now, you’re feeling you’re a sitting duck—like there’s no way to protect your baby from other people’s decisions,” said Nuzzo.

Some doctors in and around Spartanburg have started offering the shot earlier than twelve months, which means children would still require two additional shots later in life. “It’s something we’ve always done for people who are traveling to parts of the world where there’s still a high risk of measles—now we’re doing it in our own country,” Martha Edwards, president of the state’s American Academy of Pediatrics chapter, told me last week.

Ignorance and identity. But getting people to vaccinate themselves or their kids is increasingly a struggle, Edwards said, especially in places where opposition to vaccination has become a signifier of political identity and where trusted leaders aren’t forcefully speaking out for vaccination. She said she was particularly disappointed that Henry McMaster, the Republican governor, declined to mention the outbreak in last week’s State of the State address.4

“I wish that vaccines and science would not have become so politicized, and it seems like it’s been intentionally politicized,” Edwards said. “It’s been very frustrating and demoralizing to pediatricians across our state.”

One South Carolina Republican who has spoken out for vaccines is Josh Kimbrell, a state senator representing the Spartanburg area.

“It’s crazy,” Kimbrell told the Washington Post’s Lena Sun. “The number just keeps climbing. I’m deeply concerned about an eventual death.” He has called the outbreak a public health “crisis” and urged the school district to issue religious exemptions more carefully, while trying to walk a fine line and reassure skeptics he still supports parental choice.

Kennedy and President Donald Trump could give Republicans like Kimbrell some much-needed political cover—and detach the issue from the partisan politics infecting so many other parts of American life—by making loud, clear calls for vaccinations. During Trump’s first term, members of his own team did just that in response to some more limited outbreaks.

But that was an eternity ago in political time, before Kennedy was in charge and Trump was giving him full backing—not just for anti-vaccination talk, but for directives like the one HHS issued in December that will make it harder for authorities to scrutinize religious exemptions in the way Kimbrell has suggested.

Kennedy’s junk science. It’s difficult to imagine anything except raw political pressure—and, eventually, new leadership—changing the messages and policies coming from Washington, D.C. One person trying to make that happen from South Carolina is Democratic Senate hopeful Annie Andrews, who happens to be a pediatrician.

“I learned about it in textbooks as a historic disease—there’s this one picture of this little boy with a bowl cut with measles that we all saw, he’s got the rash spreading head to toe,” Andrews told me last week, recalling her medical education. “Never in my wildest dreams did I envision that this would be something that I would have to be really up to date on how to diagnose.”

Andrews is also a mother of three, and says that experience makes her even more furious about what Kennedy is doing:

You’ve got a weary-eyed mother of a four-month-old baby who’s up in the middle of the night nursing their infant, trying to decide how to protect them from measles—scrolling on their Instagram feed, and they see posts from grifters who are following RFK Jr.’s lead talking about how the vaccine is not safe and not effective, and how natural immunity is far superior, and all of these falsehoods. . . . It’s very difficult for parents to determine which information to follow, and that’s just been made worse by the fact that now this disinformation has our federal government’s fingerprints on it.”5

As the measles outbreak in her state worsens, Andrews sees a political upside to making Kennedy’s policies a campaign focus—and she’s apparently not the only Democrat thinking along those lines.

Josh Shapiro, the Pennsylvania governor widely assumed to be eyeing a White House run, went after Kennedy when the secretary visited his state recently. “RFK Jr. has made our country less healthy and less informed, and he’s spent his entire time as Secretary causing chaos and spreading misinformation,” Shapiro tweeted, along with a video trashing what he called Kennedy’s “junk science.”

Those weren’t the first barbs Shapiro sent Kennedy’s way. Last September, Shapiro decried the “total and complete chaos” Kennedy was unleashing and vowed to maintain strong vaccine guidelines in Pennsylvania.

It’s not hard to imagine Shapiro or other Democrats folding similar attacks on Kennedy’s policies into a broader assault on the GOP health care agenda, including the highly unpopular cuts to Medicaid Republicans enacted last year and their refusal to extend the extra Affordable Care Act subsidies that expired on December 1.

The talking points write themselves: Democrats could tell voters that Trump, Kennedy, and the Republicans are making it easier for Americans to get sick while making it harder to see the doctor.

And that if Republican policies stay in place, an outbreak like the one in South Carolina could very well be coming to a neighborhood near you.

1-Update (February 1, 2026, 10:00 a.m. EST): This sentence has been clarified since this article was originally published, to better explain the real-life symptoms of measles.

2-If you care about or follow public health, I highly recommend subscribing to the newsletter, which Jetelina founded.

3-Healthbeat has a timeline and chart laying this out clearly.

4-Edwards told me she brought up the issue directly in a meeting with one of the governor’s top health care advisers and was told McMaster felt the existing public health messaging was sufficient. The governor’s office did not respond to my requests for comment.

5-Lindsey Graham, the four-term Republican incumbent Andrews would presumably face if she gets the nomination, has not had much to say about the outbreak or vaccination. In fact, I couldn’t find a single comment in the public record—and his office did not respond when I asked about it.

Health and science journalist and author Jonathan Cohn writes “The Breakdown” newsletter for The Bulwark. Subscribe here.

Image: Photo illustration by Fast Company.

Measles spiked two years ago, and last year. And I don’t know if I’d call it a spike. Cool story

I am very sensitive to this subject; I got a bad case of measles when I was 4 or 5 years old (before vaccine.. 1948/. Fever was intense, and I lost my hearing by age 6. Learned to lip-read and struggled it out through high school/college, a career of diving/ocean exploration and public lecturing. Now there are fabulous electronic devices for ears, which I jumped at, at age 81. It pains me to think that our country would go backward, to where kids experience what I did -needlessly. Hillary Hauser