A Litany of Failure: Three Years into New Literacy Program, SBUSD Still Neglects and Disdains Students Desperate for Help

In their own heart-breaking words, public school students who struggle to read tell the story of the educational suffering inflicted by bureaucratic indifference and administrative fecklessness

By Cheri Rae Newsmakers Education Correspondent

On Aug. 5, I prepared and presented public comment at a school board meeting — but the words I spoke were not my own. Instead, I gave voice to insights shared with me by Santa Barbara Unified School District students.

Children ranging from second-grade to high school who want to read, but have not been taught the necessary skills to become proficient readers, despite their hard work, good intentions, and support at home.

Our highly-educated community has somehow normalized the longstanding issue that only 50 percent of our students learn to read proficiently in our schools. This despite voluminous research showing that with appropriate instruction and targeted intervention, 95 percent of students can achieve grade-level reading proficiency— an almost undreamed-of huge leap forward in literacy locally and across the country.

The community may be virtually silent on the subject of the universal right to read, but struggling students, certainly are not. They are quite articulate in describing their classroom experiences if anyone wants to listen.

“I know I’m smart, but I just can’t read,” one told me. “So then I think I am really dumb.”

An emergency in plain sight. I’m well into my second decade as an advocate for these kids on the wrong side of the reading proficiency statistics.

They have many reflections to share about their plight, if only it mattered. It’s unbelievable that this crucial aspect of a decent education isn’t treated like the emergency it is in individual lives.

Here is a sampling of comments from students who had every right to believe they would learn to read in our local classrooms in a timely matter. Now that they haven’t, they personally bear the consequences of decisions, timelines and excuses made in the board room and carried out by administrators and educators on our campuses and classrooms:

“When it’s hard to read, every school year feels like three.”

“The teachers call it ‘SSR—Silent Sustained Reading. I call it ‘Sit down, Shut up, and pretend to read.’ But mostly I look out the window and wish I was somewhere else.”

“Reading makes me feel like a piece of meat that they’re trying to tenderize, but I’m already burning up on the barbecue.”

“I want to be a scientist but I can’t be if I don’t know how to read.”

“Sometimes when I do math problems, with lots of words I can’t understand, I just want to cry.”

“I have felt so stupid for so long because I can’t read. The shame of leaving my classmates to go to the special class is a lot.”

“I’m just so tired of being the dumbest kid in the class.”

“When the teacher asked me to read what’s on the board, I told her I have some trouble with my eyes, and couldn’t see the words too well. I didn’t want to sound stupid and say that I actually can’t read the words.”

“When you’re taking a test, you’re telling yourself ‘Catch up, catch up,’ and then someone is done and they get up and leave. I don’t want to be the last person taking the test so I hurry up and I don’t want to check my work.”

“I just kind of figured out that school really isn’t for kids like me who struggle to read.”

“All I could ever think of when the class is supposed to read out loud is ‘Please don’t call on me. Please, just don’t call on me.’ Sometimes I just say I have a stomachache and need to go to the nurse’s office to get out of it.”

“I hate high school. I feel so stupid. I’m never going to be able to get through.”

The third grade imperative. Reading is fundamental for academic success in every subject, including math, history, and science.

After I read as many of those comments that fit into the three minutes allotted at the recent board meeting, another mother took her turn at the lectern and addressed the board, stressing the imperative for children to learn to read by third grade so they can then read to learn.

She described her third-grade child’s increasingly worrisome reading difficulties, and her many unsuccessful attempts to have them addressed by educators on his school campus—all the way up to the principal.

And then she began to cry.

It’s a most human reaction to bureaucratic inaction. I’ve witnessed it many times in that boardroom, as mothers and fathers are overcome by expressing their fears in public, speaking truth to power and hoping that bringing critical unsolved issues to the attention of the people we elect to represent the public’s interest in the district will somehow help.

But, as so often has happened in the past, the urgency of this child’s situation appeared to have little effect on administrators or board members.

It was a heartbreaking moment met with studied neutrality by officials seated in the bureaucratic setting with the incongruous mission statement emblazoned on the wall:

“We prepare students for a world that has yet to be created.”

For those of us well-acquainted with the reality of endless struggles, the district’s platitudes — “Every Child. Every Chance. Every Day,” they promise - ring hollow.

Empty promises of reform. Santa Barbara Unified is entering the third year of its three-year-plan for adoption of new English Language Arts curricula based on the Science of Reading, intended to address the issues raised so eloquently by it students.

But effective implementation is profoundly slow going, for many reasons.

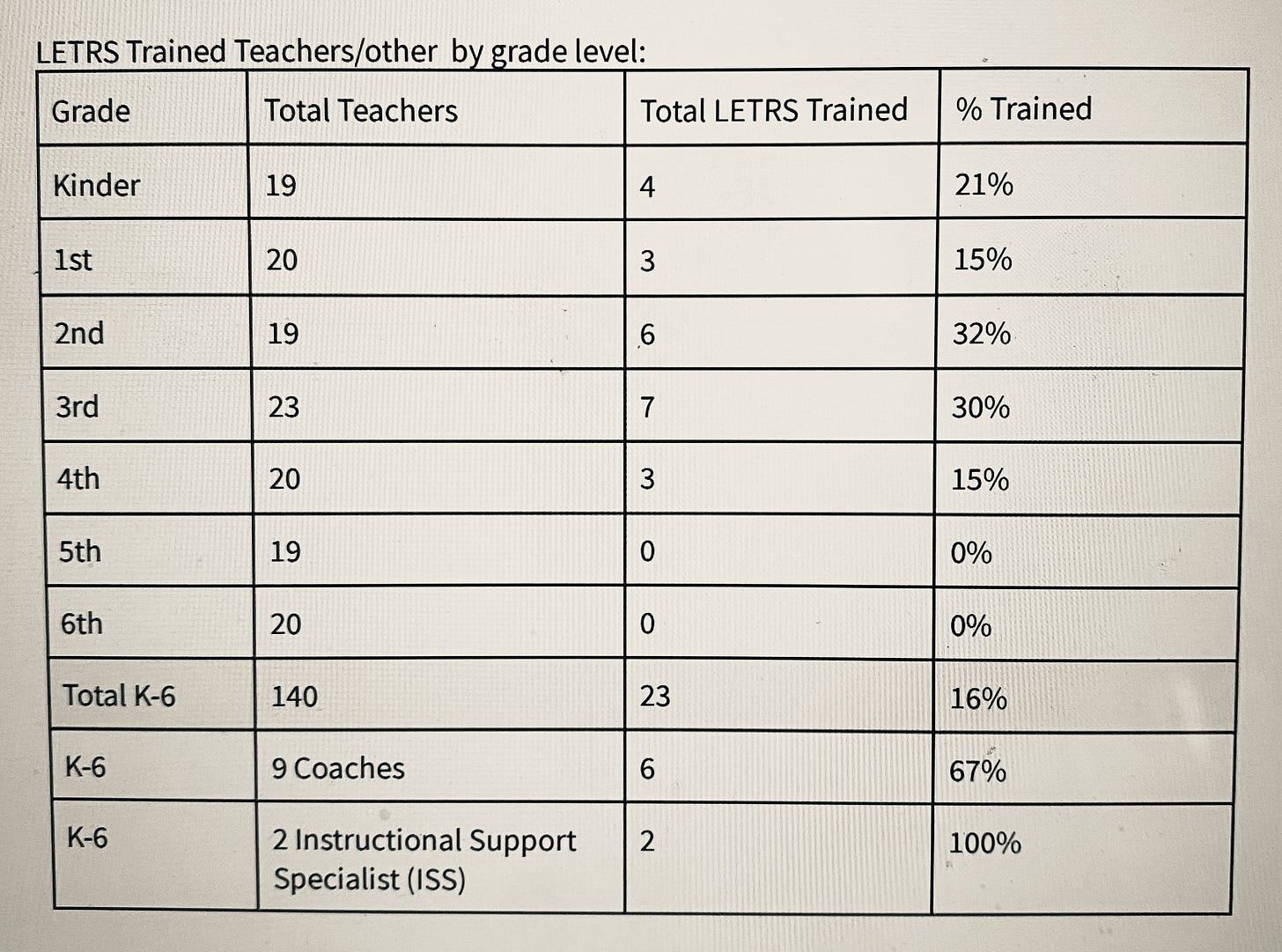

For starters, the teachers' union contract makes the intensive professional development known as “Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling” — LETRS — voluntary rather than mandatory; no surprise, the number of educators choosing to sign up for it has been lower than expected.

Also, the district depends on philanthropic support to fund the materials, training and $4,000 stipends for teachers who complete of the course of study.

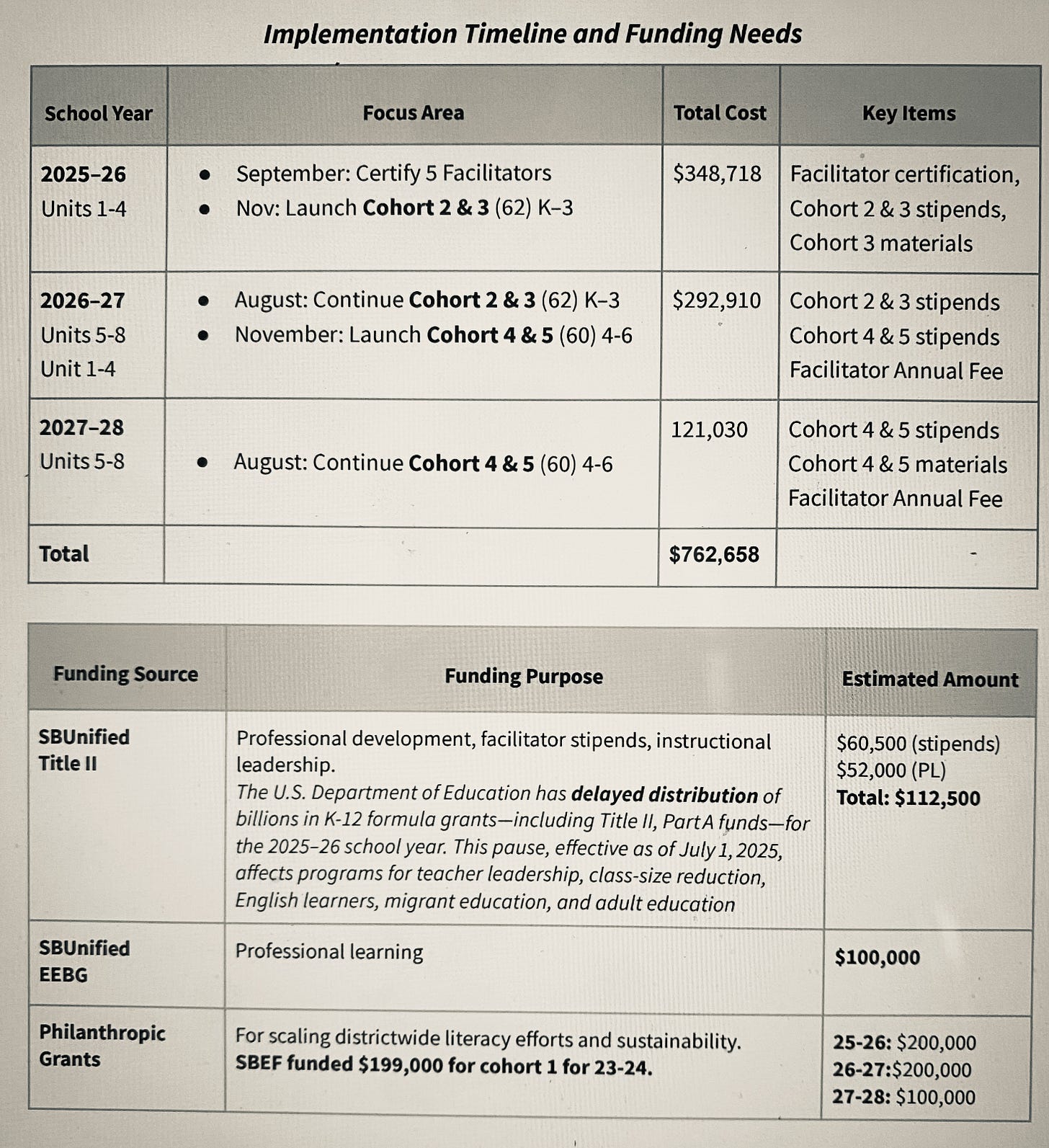

District officials now estimate it will take another three years before the training is completed by classroom teachers and their support staff. In response to questions, administrators could not say how long it will take to reach one hundred percent participation in the critical training.

Most concerning: in this first two years, only 16 percent of teachers have been trained in LETRS, at a cost of $199,000 funded by the Santa Barbara Education Foundation. Here’s the breakdown, according to district documents:

And here’s the plan for the next three years:

No word yet about how this will affect which students, in which grades, or what efforts will be made to speed up the process so more teachers will be properly trained to teach the lessons of the new curriculum.

Also unsaid is the critical need to address the students in grades 5 and 6 — who have had no teachers trained in LETRS — or in secondary school grades 7 to 12 where students have missed the Science of Reading instruction altogether.

Failure seeps into their souls. Students will continue to do their best, as they keep waiting for the adults to learn what they need to know in order to teach them to read.

Their standardized test scores won’t likely improve much, and neither will their self-esteem, as their repeated failure seeps into their souls and defines their spirits. School year after school year.

Parents, too, will do everything they can think of to express the urgency of the situation; like the mother who cried in despair, they most likely will be met by stone-faced officials unmoved by her reality.

My own son had his spirit broken when he was repeatedly required to stay in the classroom during recess to read out loud and write spelling words on the board while his friends got to play. This was at a well-regarded local elementary school he attended briefly; years later he still refers to that campus as "that jail for kids you sent me to."

And this is all just business as usual as district officials simply explain away all the reasons why only half the students entrusted to them learn to read proficiently—and never even hear the voices of those who were never taught at all.

It’s the difference between the district apparently having all the time in the world, and the kids who have no time to waste. And the effects last a lifetime.

Had enough? So have I.

Learn More

Cheri Rae, director of The Dyslexia Project, is a founding member of the Santa Barbara Reading Coalition (www.SBReads.org).

On October 18, 2-4 at the Faulkner Gallery at the Central Library, the group will host Todd Collins, highly regarded for his leadership as a former school board trustee at Palo Alto Unified and the founder of the California Reading Coalition.

His presentation will be the first in a series of community events featuring speakers who will share their experiences implementing the science of reading by adopting proven strategies and best practices in districts with demographics similar to those of Santa Barbara Unified.

Further Reading

Cheri Rae has been writing about literacy and the need for reform in how reading is taught in Santa Barbara schools for Newsmakers since 2018. Links to some of her work:

Oct. 10, 2018. “Why SBUSD Falls Short on Reading.”

Sept. 25, 2021. “Literacy Denial: As the Climate Changes on Reading Instruction, We Must Respect the Science.”

May 25, 2022. “SB County’s 50% Student Proficiency is a Scandal.” (with Monie DeWit).

March 21, 2023. “Pigs Fly: SBUSD Finally Pivot from ‘Balanced Literacy’ to ‘Science of Reading.” (with Monie DeWit).

Oct. 8, 2024. “Dispatch from DyslexiaLand: The Ongoing Struggle for the Right to Read.”

Image: Catch Up and Read.

Thank you Jerry Roberts. Also thank you Cheri Rae for advocating tirelessly and giving voice to what's happening to thousands of students in our district because the system and many adults are sadly apathetic or unwilling to create an effective implementation for the science of reading approach so all students can read proficiently and have the ability to reach their dreams.

Kudos to Cheri for banging this drum once again. Every single child should have the benefit of the necessary help they may need in order to learn to read. All the parents in our community pay taxes for this purpose. Therefore no child should be left out.